Education/Research

National Heritage Story

January 17, 1953~ | Bearer Recognition : December 31, 1996

Ox Horn Inlaying

Hwagakjang, Painting on Bull Horns with Their Soul

Hwagak refers to the practice of grinding horns into thin, paper-like see-through sheets, painting on them with colors, and attaching the base to the surface of wooden objects to decorate them, and the artisans who specialize in this craft are called hwagakjang. This technique originated from the daemobokchae decoration technique, which dates back to the Tang dynasty in China. The technique of grinding the carapace of hawksbill sea turtles found in tropical and subtropical regions into thin slices and attaching them to the surface of woodwork as ornaments was introduced to Unified Silla, which traded extensively with the Tang dynasty, and it continued to be practiced throughout the Goryeo dynasty and even in the Joseon dynasty. However, there are no artifacts or written records in Korea to prove this. The only references available are the Daemobokchaekaljip sword sheathe from the Unified Silla period housed in Shosoin, an ancient treasure chest of Japan, and daemojeon, which was used in combination with mother-of-pearl patterns in the Goryeo and Joseon periods on lacquerware.

This daemojeon technique was popular before the middle of the Goryeo dynasty, but gradually declined due to the difficulty in obtaining imported hawksbill sea turtles, as well as the fact that the turtles were used not only as a material for making combs and jewelry but also as an important medicinal ingredient in oriental medicine. Hawksbill sea turtle shells became increasingly scarce due to high demand and were eventually replaced by bull horns, and the craft of hwagak flourished during the Joseon dynasty around the 18th century. However, hwagak crafts dating back before the 18th century cannot be found due to decay, based on which it is inferred that the practice of using bull horns began before the 18th century. The reason why it has been possible for this craft to have been passed down to the present day is that Eum Il-cheon, a third-generation gakjiljang and daemogongjang since the late Joseon dynasty (during the reign of King Gojong) devoted himself to the production of hwagak crafts since the early 1920s based on research and training in the techniques of hwagakjang, and continued to produce related works until the early 1970s. Lee Jae-man, who learned the techniques from Eum Il-cheon, has since been recognized as a bearer of hwagakjang, designated as a national intangible cultural heritage.

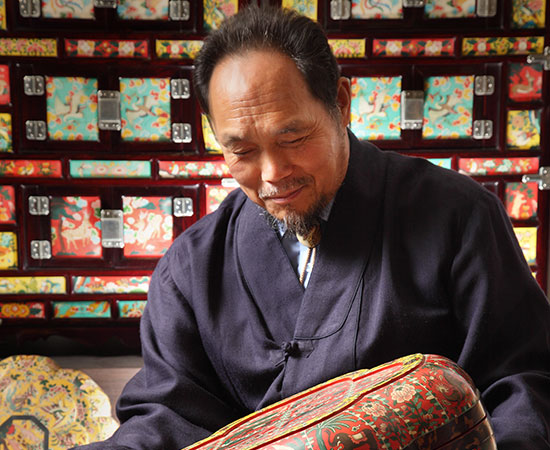

Hwagakjang Lee Jae-man

Hwagakjang Lee jae-man was born in 1953, the youngest of four sons and one daughter, to Mr. Lee Geum-dal, a daemokjang (his grandfather was a dancheongjang), and Ms. Jeong Gyeong-hee, an accomplished embroiderer, and grew up in Seongsu-dong, Seoul. When he was just over a year old, Lee was severely burned when he fell on an open flame and was not properly treated, leaving him with only a few intact fingers and the rest missing a digit or two. Nevertheless, he had a knack for drawing and won several prizes in the National Art Competition during his elementary school years.

His father died when he was just three and he was raised by his mother. When he was sixteen, he was introduced by a friend to Eum Il-cheon’s workshop and began training under his tutelage. He had a difficult time, working in the day and studying at night at such a young age. For the first year and a half, he was selected as an assistant to Lee Sang-ho, a popular cartoonist at the time. He enjoyed drawing cartoons and even had a side job drawing theater signs, while neglecting his training in hwagak. However, dabbling in other areas actually increased his awareness of the value of hwagak craftmaking, and he began to think about his future career path and finally became committed to honing his hwagak skills under the instruction of Eum Il-cheon.

A sudden fire at the Hail-dong workshop, coupled with his teacher’s quadriplegia, forced the workshop to close, and Lee Jae-man began working independently. At the request of Professor Jeong Myeong-ho, a lecturer at Wonkwang University who often visited Eum Il-chun’s workshop for a theoretical study on hwagakjang crafts, Lee Jae-man began making hwagak crafts at the professor’s home around 1971. Then, in 1984, he served as the head of the hwagak workshop of the Intangible Cultural Property Training Center (the predecessor of the current Training Center for Important Intangible Cultural Properties) in Samseong-dong, while also making his own works. He has won prizes at various craft exhibitions, including the Korea Annual Traditional Handicraft Art Exhibition, and has also been involved in educational activities, lecturing on the art of hwagak at the Korean School of Traditional Crafts and Architecture (an educational institution affiliated with the Korean Museum of Traditional Handicrafts located in Gyeongbokgung Palace) run by the Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation,

In 1996, Lee Jae-man was recognized as a bearer of the national intangible cultural heritage, hwagakjang. He is also keen on the development of a wide variety of cultural products, with an interest in introducing everyday hwagak items. The diversification of crafts leads to their everyday use, and considering that the traditional works in the past were practical items used daily, the development of items with various everyday applications is a step forward in the spirit of craftsmanship.

Works

- Hwagak Gujeolpan (Platter of Nine Delicacies), 34×10 cm

This is a wooden platter divided into nine compartments to hold nine different food ingredients. Sipjangsaeng (ten symbols of longevity) was depicted to wish the user a long, healthy life.

- Hwagak Sajuham, 59x33x34 cm

- Hwagak Seoryuham (Document Filing Box), 36.5x28.5x12 cm

- Hwagak Jwagyeong (Mirror), 26x34x23 cm